Is rage the bridge between pain and rebellion?

At what point does anguish, despair, helplessness turn into rage?

Insurgent Captain Marcos

Mexico, December 2023

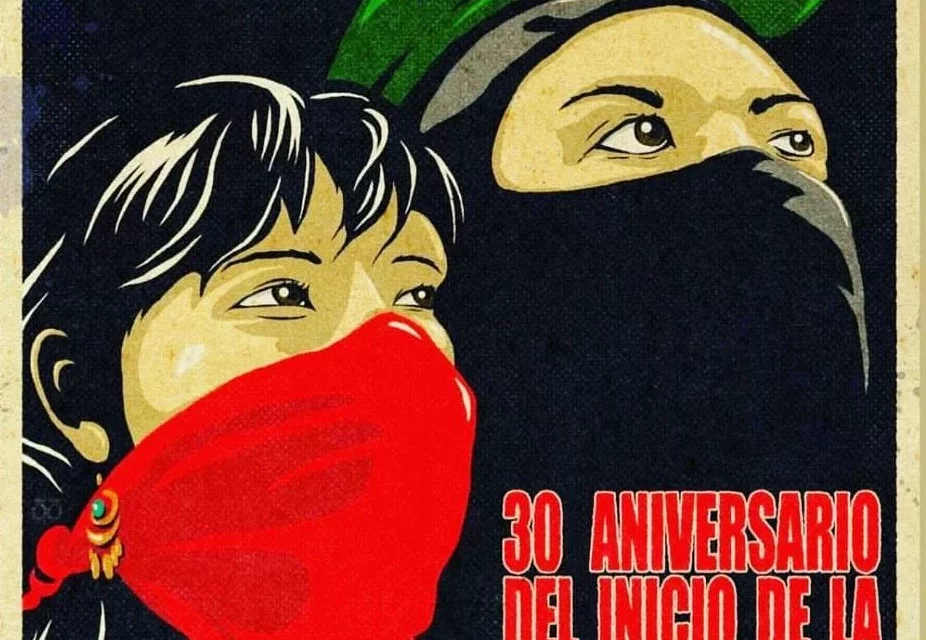

January 1, 2024 marked 30 years since the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) declared war on the Mexican State. That day holds a special place in the memory of thousands of people in Mexico and the world. It was a historic event that closed the 20th century and inaugurated the 21st. The Zapatista uprising is part of a series of struggles by those from below that opened a new cycle of revolts.

I

The Zapatista rebellion emerged at a time when the ruling classes were flooding the world with their narratives of the end of history and trying to impose the idea that there is no alternative to neoliberal capitalism and its civilizing project. The fall of the Soviet bloc further fueled the disenchantment of those who still clung to that alternative that had long since ceased to be.

In Latin America the story was different. In the 1980s, a process of anti-neoliberal mobilization was taking shape in the region. Popular, peasant and indigenous organizations carried out important demonstrations against the waves of privatization, the dispossession of common goods and the elimination of social rights. The era of dictatorships and state terrorism, with its savage repression and thousands of deaths and disappearances, did not succeed in destroying the rebellious conscience of peoples and communities. It was a rebellion forged from below against the global recolonization of capital, a recolonization undertaken by states and corporations.

This process of popular anti-neoliberal insurrection gained new strength in the 1990s, especially in 1992. That year, the native and Afro-descendant peoples emerged with all their power and experience of resistance to centuries of colonial and imperialist domination and also to the internal colonialism of the nation-states. Centuries of struggle had protected them, but this time they appeared as a socio-political subject throughout the continent. The celebrations of the 500th anniversary of the discovery and conquest of America were overshadowed by a gigantic movement commemorating 500 years of black, indigenous and popular resistance. In Ecuador, Bolivia, Guatemala and many other Latin American countries, the people came out to tear down myths and statues, and to tell the whole world: we exist because we resist. In Mexico, in the state of Chiapas, the people who had been organizing clandestinely since 1983, also participated in that wave of mobilizations. A deep crack in the system was beginning to become visible.

If the public appearance of the EZLN in 1994 gave the indigenous movement in Mexico a national projection, with spaces for meeting, dialogue and agreements, and placed its demands on the country’s public agenda, the Zapatista movement helped the internationalist left to break with the dominant narrative and to give itself new meanings. Faced with the No Alternative that Margaret Thatcher and the neoliberals repeated as a mantra, thousands of people around the world opposed the Other World is Possible. In Seattle, Genoa, Porto Alegre, Madrid and in so many other places on the planet, alterglobalization found in Zapatismo a mirror in which to look at itself and to look beyond. The anti-neoliberal movement that spread throughout the world, and which had a multisectoral and ideologically diverse composition, also found in the EZLN a common language to name hope.

The cry of “Enough is enough! launched by the Mayan Zapatista peoples was a cry that was assumed as their own in Mexico and part of the world. And that cry had major repercussions. A form of cultural change was beginning to take shape. The Zapatista rebellion was taken to literature, music, cinema, photography, dance, theater… Manu Chao, Joaquín Sabina, Danielle Miterrand, Oliver Stone, Eduardo Galeano, José Saramago and so many more became interlocutors of a message that, in the voice of Zapatismo, was the message of thousands. People of very diverse ages, professions and geographies came to Chiapas to try to help give birth to the new world that was being born. The seed of a new political culture, of an other politics strongly intertwined with ethics, began to blossom. An other politics born of rage at 500 years of oppression and exploitation. And with the dignified rage also came a new springtime. Another world was possible.

II

If outside Chiapas the echo of Zapatismo helped to change the ways of thinking, doing and speaking in politics, laying the foundations of a cultural and generational change that still impacts today and that Immanuel Wallerstein himself would link with the changes produced by the cultural revolution of 1968, on the inside, that is, in the Zapatista Mayan communities, the change was not only cultural, but also linked to a material change. This material and cultural change in the Mayan Zapatista communities could well be defined as a revolutionary change, in the sense that it recovers the means of production -the land-, eliminates the bureaucratic apparatus and builds good government from commanding by obeying, and expels the repressive apparatus of the State from their territories and builds a people-army, an army that wants to stop being an army.

But the Zapatistas, who know well the weight of words and who have gained much recognition for their congruence in thinking-saying-doing, call their process one of Resistance and Rebellion, a creative resistance that is not just “getting tough,” as Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés, spokesman for the EZLN, has said, but also imagining and creating solutions to the problems that arise daily in their process. To this creative resistance, the Zapatistas add a rebelliousness, which is “to be brave women and men in order to respond in the same way or to take action, according to what is appropriate, so we have to be brave in order to take action or do what we need to do,” as Sub Moisés himself also said. And that rebelliousness, besides being joyful, is also critical, self-critical and supportive; a rebelliousness that understands, among other things, how powerful it is to dance cumbia in the struggle against the system.

With this Resistance and Rebellion, the Zapatista peoples have built an autonomous project based on the recovery of lands previously usurped by landowners, farmers and large landowners. This process has been described in detail by Sub Moisés in his interventions on Political Economy from the Communities I and II:

One of the bases of what is our economic resistance for us, we, the Zapatistas, is mother earth. We don’t have those houses that the bad government gives us, blocks and all that, but we do have health, we have education, we are in the sense that it is the people who command and the governments obey.

The recuperated lands became the material basis for the construction of autonomy. With the family and collective work of the lands, good food and housing were guaranteed. Schools and health clinics were built. Productive projects were launched. Security and justice systems were implemented, as well as self-government structures. Community radio stations were strengthened and new media were explored. Alternative banks, transportation cooperatives, livestock cooperatives, embroidery cooperatives were created… All without receiving a single peso from the Mexican governments, which during these 30 years have not stopped waging open and covert war, with official or paramilitary forces, against Zapatismo.

Thirty years ago, in Zapatista territory, children died of curable diseases due to lack of medicine. Today, in Zapatista communities there are health promoters, with health houses, clinics and hospitals, where they combine traditional knowledge and modern medicine.

Thirty years ago, thousands of indigenous children and youth were illiterate and had no educational options. Today, thousands of Zapatista children and youth have access to the schools that the Zapatista peoples have built and to the education that the promotoras and promotores provide them.

More than 30 years ago, indigenous women were raped by caciques, landowners and ranchers, or were forced to marry whoever their families agreed to. Today, Zapatista women are a fundamental part of the organizational structure. With the Law of Revolutionary Women, since December 1993, this commitment to the Zapatista struggle became clear and is now a reality. There are women commanders, sub-commanders, captains, elders, but also health and education promoters; they are community authorities, they choose who to love and if they want to get married or not, they sing rap, hip hop and, for some time now, they have been a global reference for women in the struggle.

The material and cultural change within the Mayan Zapatista communities is an undeniable fact and contrasts with the voracity with which capitalism has advanced in Mexico. In this country, where there are more than 100,000 disappeared persons, no disappearance has occurred in Zapatista territory. None of the 10 femicides that occur daily in Mexican territory occurred in Zapatista territory. In Zapatista territory there is no organized crime, there are no mining or water concessions, there is no human trafficking. In Zapatista territory, where the people command and the government obeys, the lives of people and nature are taken care of.

III

Throughout 30 years, the Zapatista rebellion has been the object of numerous investigations. Many of these works seek to analyze Zapatismo from a diversity of approaches, perspectives and political and theoretical approaches that are difficult to classify due to their great quantity. They are materials elaborated by people dedicated to very different professions and activities: academia, political militancy, journalism. There are also the investigations of the intelligence apparatus of the Mexican State which, either directly or through mediation, has disseminated adverse or defamatory information against the EZLN. This information of police origin became, from the first years, the center of the public opinion matrices with which they sought to counteract the legitimacy of Zapatismo; a strategy that, with its variations, has been reused on various occasions.

But the Zapatista peoples are not objects, they are subjects who speak, think, act, who reflect on their organizational practice. Thus, they provoke an epistemological subversion: they are subjects who reflect on what they do and say. They construct concepts. They retrieve data, compile information, analyze it and put forward hypotheses. They have a method. Their gaze breaks with the here and now, with the presentist dictatorship of our time. They go from the local to the global: they see their communities, their regions, their zones, Chiapas, Mexico, America, the World. They know they are part of something greater.

Their time is also another time. They look to the past to project themselves into the future. They talk to their dead and appeal to memory. They imagine what may come. They read, listen, inform themselves and consider worst-case scenarios. They calculate what to do to survive. They have their telescopes and sentinels -Immanuel Wallerstein and Pablo González Casanova were some of them-, and they rely on them to see beyond what their eyes can reach.

A primordial source to enter into the Zapatista theory and praxis is the Historical Archive of the Enlace Zapatista web page, where one will find fundamental documents such as the six declarations of the Lacandon Jungle, the Notebooks of the Zapatista Escuelita, the Zapatista word in the conversation The Critical Thought in the Face of the Capitalist Hydra, the Revolutionary Law of Women, the Declaration for Life, writings on war and political economy.

With this theory and praxis, the Zapatista peoples have been alerting us for some time about what they can see and also about how they are constructing solutions: The land problem was never only a problem of peasant sectors and native peoples. Today, the problem of land and territory, of those who own it and those who privatize it, is a problem of humanity. Those who have dispossessed the peoples of their land and territories, in their eagerness to generate maximum profits, have destroyed it and have us in the midst of collapse. Those who have made the land a commodity are the same people who have made life another commodity.

Progress built under the idea of the domestication of nature, of domination, is not only built under an assumption of superiority and independence, but under an idea of infinity. But, as Frederick Engels said almost 140 years ago, “After each of these victories, nature takes its revenge.” Today the Zapatistas tell us: Mother Earth “protests”, she “manifests” in the face of so much destruction. This conclusion of the peoples coincides with the most advanced scientific knowledge, those that the lords of money invest millions to deny. Climate change, ecocide, is a reality. The natural phenomena that turn into social disasters, the pandemics, the thousands of species that disappear, the climate migrants and many other tragedies are just the beginning of the collapse in the making.

But this ecocide is not natural; behind the destruction of life is a system of death that in its logic of profit maximization has turned everything into commodities. And along with climate change caused by capitalist devastation, there are also other systems of domination and exploitation that are just as urgent to address, such as patriarchy, racism, organized crime. Zapatismo alerts us to all these problems through its theory and praxis.

The world is sick and must be cured. But we must cure it seriously, not with placebos. And to this end, the Zapatistas warn us: “capitalism cannot be humanized,” there is no possibility of an alternative from within. In the face of this, they are now launching a bold, novel initiative that is still difficult to understand. The commons and non-ownership. An initiative in which they embark to transit and survive the storm. The crack they opened 30 years ago is today a door. They will continue to talk to us about it. Let us listen attentively to those who have been committed to defend life for so long. Their voice can be light in the midst of so much darkness.

Raúl Romero is a university professor and academic expert at UNAM’s Institute for Social Research.

Original article by Raúl Romero published by Viento Sur on April 18th, 2024.

Translation by Schools for Chiapas.